Introduction

One of the main tasks for OpenDreamKit (T.31]) is improving portability of mathematical software across hardware platforms and operating systems.

One particular such challenge, which has dogged the SageMath project practically since its inception, is getting a fully working port of Sage on Windows (and by extension this would mean working Windows versions of all the CAS’s and other software Sage depends on, such as GAP, Singular, etc.)

This is particularly challenging, not so much because of the Sage Python library (which has some, but relatively little system-specific code). Rather, the challenge is in porting all of Sage’s 150+ standard dependencies, and ensuring that they integrate well on Windows, with a passing test suite.

Although UNIX-like systems are popular among open source software developers and some academics, the desktop and laptop market share of Windows computers is estimated to be more than 75% and is an important source of potential users, especially students.

However, for most of its existence, the only way to “install” Sage on Windows was to run a Linux virtual machine that came pre-installed with Sage, which is made available on Sage’s downloads page. This is clumsy and onerous for users–it forces them to work within an unfamiliar OS, and it can be difficult and confusing to connect files and directories in their host OS to files and directories inside the VM, and likewise for web-based applications like the notebook. Because of this Windows users can feel like second-class citizens in the Sage ecosystem, and this may turn them away from Sage.

Attempts at Windows support almost as old as Sage itself (initial Sage release in 2005). Microsoft offered funding to work on Windows version as far back as 2007 but was far too little for the amount of effort needed.

Additional work done was done off and on through 2012, and partial support was possible at times. This included admirable work to try to support building with the native Windows development toolchain (e.g. MSVC). There was even at one time an earlier version of a Sage installer for Windows, but long since abandoned.

However, Sage development (and more importantly Sage’s dependencies) continued to advance faster than there were resources for the work on Windows support to keep up, and work mostly stalled after 2013. OpenDreamKit has provided a unique opportunity to fund the kind of sustained effort needed for Sage’s Windows support to catch up.

Sage for Windows overview

As of SageMath version 8.0, Sage will be available for 64-bit versions of Windows 7 and up. It can be downloaded through the SageMath website, and up-to-date installation instructions are being developed at the SageMath wiki. A 32-bit version had been planned as well, but is on hold due to technical limitations that will be discussed later.

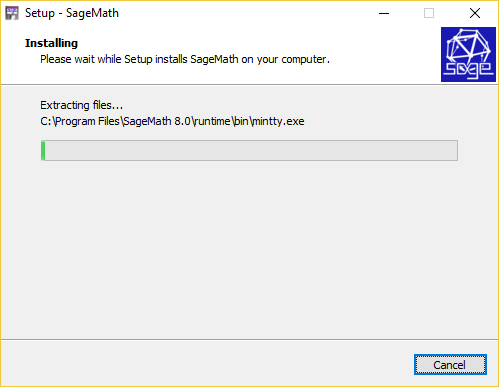

The installer contains all software and documentation making up the standard Sage distribution, all libraries needed for Cygwin support, a bash shell, numerous standard UNIX command-line utilities, and the Mintty terminal emulator, which is generally more user-friendly and better suited for Cygwin software than the standard Windows console.

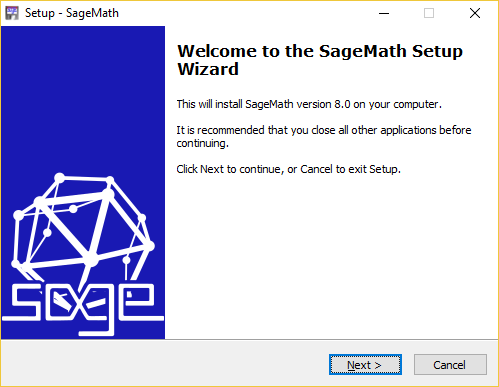

It is distributed in the form of a single-file executable installer, with a familiar install wizard interface (built with the venerable InnoSetup. The installer comes in at just under a gigabyte, but unpacks to more than 4.5 GB in version 8.0.

Because of the large number of files comprising the complete SageMath distribution, and the heavy compression of the installer, installation can take a fair amount of time even on a recent system. On my Intel i7 laptop it takes about ten minutes, but results will vary. Fortunately, this has not yet been a source of complaints–beta testers have been content to run the installer in the background while doing other work–on a modern multi-core machine the installer itself does not use overly many resources.

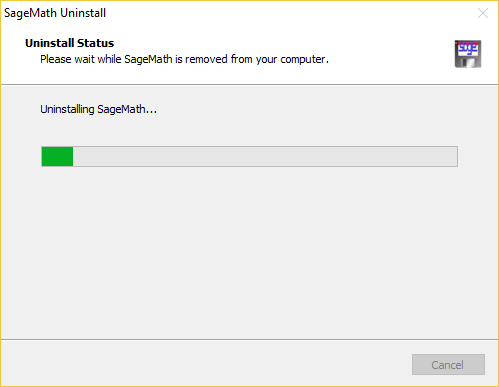

If you don’t like it, there’s also a standard uninstall:

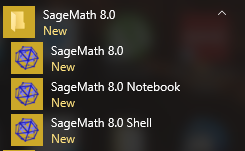

The installer includes three desktop and/or start menu shortcuts:

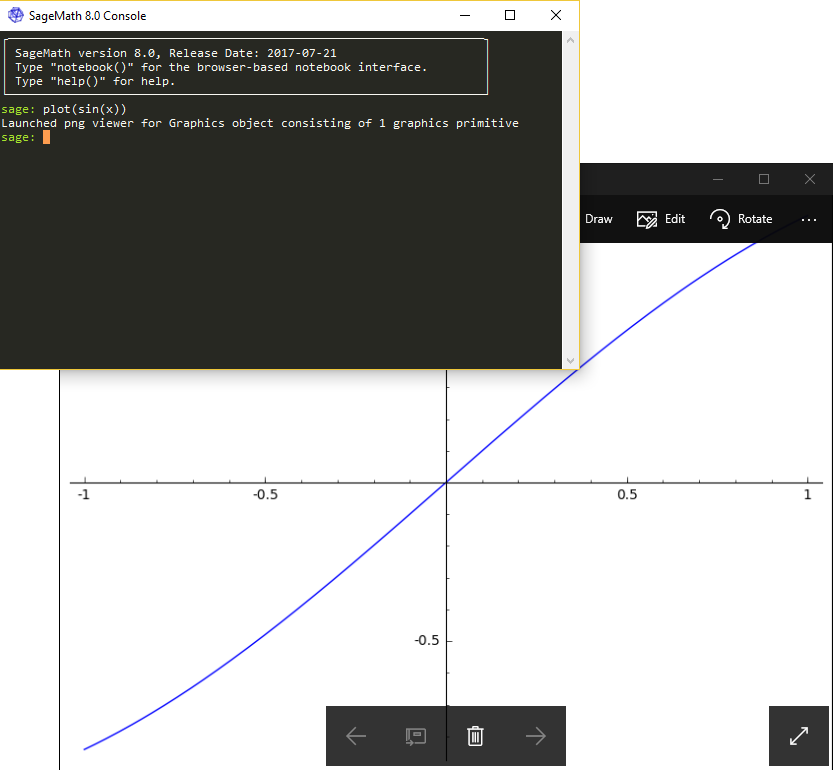

The shortcut titled just “SageMath 8.0” launches the standard Sage command prompt in a text-based console. In general it integrates well enough with the Windows shell to launch files with the default viewer for those file types. For example, plots are saved to files and displayed automatically with the default image viewer registered on the computer.

(Because Mintty supports SIXEL mode graphics, it may also be possible to embed plots and equations directly in the console, but this has not been made to work yet with Sage.)

“SageMath Shell” runs a bash shell with the environment set up to run software in the Sage distribution. More advanced users, or users who wish to directly use other software included in the Sage distribution (e.g. GAP, Singular) without going through the Sage interface. Finally, “SageMath Notebook” starts a Jupyter Notebook server with Sage configured as the default kernel and, where possible, opens the Notebook interface in the user’s browser.

In principle this could also be used as a development environment for doing development of Sage and/or Sage extensions on Windows, but the current installer is geared primarily just for users.

Rationale for Cygwin and possible alternatives

There are a few possible routes to supporting Sage on Windows, of which Cygwin is just one. For example, before restarting work on the Cygwin port I experimented with a solution that would run Sage on Windows using Docker. I built an installer for Sage that would install Docker for Windows if it was not already installed, install and configure a pre-build Sage image for Docker, and install some desktop shortcuts that attempted to launch Sage in Docker as transparently as possible to the user. That is, it would ensure that Docker was running, that a container for the Sage image was running, and then would redirect I/O to the Docker container.

This approach “worked”, but was still fairly clumsy and error-prone. In order to make the experience as transparent as possible a fair amount of automation of Docker was needed. This could get particularly tricky in cases where the user also uses Docker directly, and accidentally interferes with the Sage Docker installation. Handling issues like file system and network port mapping, while possible, was even more complicated. What’s worse, running Linux images in Docker for Windows still requires virtualization. On older versions this meant running VirtualBox in the background, while newer versions require the Hyper-V hypervisor (which is not available on all versions of Windows–particularly “Home” versions). Furthermore, this requires hardware-assisted virtualization (HAV) to be enabled in the user’s BIOS. This typically does not come enabled by default on home PCs, and users must manually enable it in their BIOS menu. We did not consider this a reasonable step to ask of users merely to “install Sage”.

Another approach, which was looked at in the early efforts to port Sage to Windows, would be to get Sage and all its dependencies building with the standard Microsoft toolchain (MSVC, etc.). This would mean both porting the code to work natively on Windows, using the MSVC runtime, as well as developing build systems compatible with MSVC. There was a time when, remarkably, many of Sage’s dependencies did meet these requirements. But since then the number of dependencies has grown too much, and Sage itself become too dependent on the GNU toolchain, that this would be an almost impossible undertaking.

A middle ground between MSVC and Cygwin would be to build Sage using the MinGW toolchain, which is a port of GNU build tools (including binutils, gcc, make, autoconf, etc.) as well as some other common UNIX tools like the bash shell to Windows. Unlike Cygwin, MinGW does not provide emulation of POSIX or Linux system APIs–it just provides a Windows-native port of the development tools. Many of Sage’s dependencies would still need to be updated in order to work natively on Windows, but at the very least their build systems would require relatively little updating–not much more than is required for Cygwin. This would actually be my preferred approach, and with enough time and resources it could probably work. However, it would still require a significant amount of work to port some of Sage’s more non-trivial dependencies, such as GAP and Singular, to work on Windows without some POSIX emulation.

So Cygwin is the path of least resistance. Although bugs and shortcomings

in Cygwin itself occasionally require some effort to work around (as a

developer–users should not have to think about it), for the most part it

just works with software written for UNIX-like systems. It also has the

advantage of providing a full UNIX-like shell experience, so shell scripts

and scripts that use UNIX shell tools will work even on Windows. However,

since it works directly on the native filesystem, there is less opportunity

for confusion regarding where files and folders are saved. In fact, Cygwin

supports both Windows-style paths (starting with C:\\) and UNIX-style

paths (in this case starting with C:/).

Finally, a note on the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), which debuted

shortly after I began my Cygwin porting efforts, as I often get asked about

this: “Why not ‘just’ use the ‘bash for Windows’?” The WSL is a new effort

by Microsoft to allow running executables built for Linux directly on

Windows, with full support from the Windows kernel for emulation of Linux

system calls (including ones like fork()). Basically, it aims to provide

all the functionality of Cygwin, but with full support from the kernel, and

the ability to run Linux binaries directly, without having to recompile

them. This is great of course. So the question is asked if Sage can run in

this environment, and experiments suggest that it works pretty well

(although the WSL is still under active development and has room for

improvement).

I wrote more about the WSL in a blog post last year, which also addresses why we can’t “just” use it for Sage for Windows. But in short: 1) The WSL is currently only intended as a developer tool: There’s no way to package Windows software for end users such that it uses the WSL transparently. And 2) It’s only available on recent updates of Windows 10–it will never be available on older Windows versions. So to reach the most users, and provide the most hassle-free user experience, the WSL is not currently a solution. However, it may still prove useful for developers as a way to do Sage development on Windows. And in the future it may be the easiest way to install UNIX-based software on Windows as well, especially if Microsoft ever expands its scope.

Development challenges

The main challenge with porting Sage to Windows/Cygwin has relatively little to do with the Sage library itself, which is written almost entirely in Python/Cython and involves relatively few system interfaces (a notable exception to this is the advanced signal handling provided by Cysignals, but this has been found to work almost flawlessly on Cygwin thanks to the Cygwin developers’ heroic efforts in emulating POSIX signal handling on Windows). Rather, most of the effort has gone into build and portability issues with Sage’s more than 150 dependencies.

The majority of issues have been build-related issues. Runtime issues are less common, as many of Sage’s dependencies are primarily mathematical, numerical code–mostly CPU-bound algorithms that have little use of platform-specific APIs. Another reason is that, although there are some anomalous cases, Cygwin’s emulation of POSIX (and some Linux) interfaces is good enough that most existing code just works as-is. However, because applications built in Cygwin are native Windows applications and DLLs, there are Windows-specific subtleties that come up when building some non-trivial software. So most of the challenge has been getting all of Sage’s dependencies building cleanly on Cygwin, and then maintaining that support (as the maintainers of most of these dependencies are not themselves testing against Cygwin regularly).

In fact, maintenance was the most difficult aspect of the Cygwin port (and this is one of the main reasons past efforts failed–without a sustained effort it was not possible to keep up with the pace of Sage development). I had a snapshot of Sage that was fully working on Cygwin, with all tests passing, as soon as the end of summer in 2016. That is, I started with one version of Sage and added to it all the fixes needed for that version to work. However, by the time that work was done, there were many new developments to Sage that I had to redo my work on top of, and there were many new issues to fix. This cycle repeated itself a number of times.

Continuous integration

The critical component that was missing for creating a sustainable Cygwin port of Sage was a patchbot for Cygwin. The Sage developers maintain a (volunteer) army of patchbots–computers running a number of different OS and hardware platforms that perform continuous integration testing of all proposed software changes to Sage. The patchbots are able, ideally, to catch changes that break Sage–possibly only on specific platforms–before they are merged into the main development branch. Without a patchbot testing changes on Cygwin, there was no way to stop changes from being merged that broke Cygwin. With some effort I managed to get a Windows VM with Cygwin running reliably on UPSud’s OpenStack infrastructure, that could run a Cygwin patchbot for Sage. By continuing to monitor this patchbot the Sage community can now receive prior warning if/when a change will break the Cygwin port. I expect this will impact only a small number of changes–in particular those that update one of Sage’s dependencies.

In so doing we are, indirectly, providing continuous integration on Cygwin for Sage’s many dependencies–something most of those projects do not have the resources to do on their own. So this should be considered a service to the open source software community at large. (I am also planning to piggyback on the work I did for Sage to provide a Cygwin buildbot for Python–this will be important moving forward as the official Python source tree has been broken on Cygwin for some time, but is one of the most critical dependencies for Sage).

Runtime bugs

All that said, a few of the runtime bugs that come up are non-trivial as well. One particular source of bugs is subtle synchronization issues in multi-process code, that arise primarily due to the large overhead of creating, destroying, and signalling processes on Cygwin, as compared to most UNIXes. Other problems arise in areas of behavior that are not specified by the POSIX standard, and assumptions are made that might hold on, say, Linux, but that do not hold on Cygwin (but that are still POSIX-compliant!) For example, a difference in (undocumented, in both cases) memory management between Linux and Cygwin made for a particularly challenging bug in PARI. Another interesting bug came up in a test that invoked a stack overflow bug in Python, which only came up on Cygwin due to the smaller default stack size of programs compiled for Windows. There are also occasional bugs due to small differences in numerical results, due to the different implementation of the standard C math routines on Cygwin, versus GNU libc. So one should not come away with the impression that porting software as complex as Sage and its dependencies to Cygwin is completely trivial, nor that similar bugs might not arise in the future.

Challenges with 32-bit Windows/Cygwin

The original work of porting Sage to Cygwin focused on the 32-bit version of Cygwin. In fact, at the time that was the only version of Cygwin–the first release of the 64-bit version of Cygwin was not until 2013. When I picked up work on this again I focused on 64-bit Cygwin–most software developers today are working primarily on 64-bit systems, and so from many projects I’ve worked on the past my experience has been that they have been more stable on 64-bit systems. I figured this would likely be true for Sage and its dependencies as well.

In fact, after getting Sage working on 64-bit Cygwin, when it came time to test on 32-bit Cygwin I hit some significant snags. Without going into too many technical details, the main problem is that 32-bit Windows applications have a user address space limited to just 2 GB (or 3 GB with a special boot flag). This is in fact not enough to fit all of Sage into memory at once. The good news is that for most cases one would never try to use all of Sage at once–this is only an issue if one tries to load every library in both Sage, and all its dependencies, into the same address space. In practical use this is rare, though this limit can be hit while running the Sage test suite.

With some care, such as reserving address space for the most likely to be used (especially simultaneously) libraries in Sage, we can work around this problem for the average user. But the result may still not be 100% stable.

It becomes a valid question whether it’s worth the effort. There are unfortunately few publicly available statistics on the current market share of 64-bit versus 32-bit Windows versions among desktop users. Very few new desktops and laptops sold anymore to the consumer market include 32-bit OSes, but it is still not too uncommon to find on some older, lower-end laptops. In particular, some laptops sold not too long ago with Windows 7 were 32-bit. According to Net Market Share, as of writing Windows 7 still makes up nearly 50% of all desktop operating system installments. This still does not tell us about 32-bit versus 64-bit. The popular (12.5 million concurrent users) Steam PC gaming platform publishes the results of their usage statistics survey, which as of writing shows barely over 5% of users with 32-bit versions of Windows. However, computer gamers are not likely to be representative of the overall market, being more likely to upgrade their software and hardware.

So until some specific demand for a 32-bit version of SageMath for Windows is heard, we will not likely invest more effort into it.

Conclusion and future work

Focusing on Cygwin for porting Sage to Windows was definitely the right way to go. It took me only a few months in the summer of 2016 to get the vast majority of the work done. The rest was just a question of keeping up with changes to Sage and fixing more bugs (this required enough constant effort that it’s no wonder nobody managed to quite do it before). Now, however, enough issues have been addressed that the Windows version has remained fairly stable, even in the face of ongoing updates to Sage.

Porting more of Sage’s dependencies to build with MinGW and without Cygwin might still be a worthwhile effort, as Cygwin adds some overhead in a few areas, but if we had started with that it would have been too much effort.

In the near future, however, the priority needs to be improvements to user experience of the Windows Installer. In particular, a better solution is needed for installing Sage’s optional packages on Windows (preferably without needing to compile them). And an improved experience for using Sage in the Jupyter Notebook, such that the Notebook server can run in the background as a Windows Service, would be nice. This feature would not be specific to Sage either, and could benefit all users of the Jupyter Notebook on Windows.

Finally, I need to better document the process of doing Sage development on Cygwin, including the typical kinds of problems that arise. I also need to better document how to set up and maintain the Cygwin patchbot, and how to build releases of the Sage on Windows installer so that its maintenance does not fall solely on my shoulders.