Berlin workshop

This week the KWARC team (Michael Kohlhase, Florian Rabe, Dennis Müller) and myself met in Berlin at the WIAS. The goal was to meet some of the modelers working there, who are very interested in the MMT system and the work in OpenDreamKit. Their entry point is Work Package 6 (interoperability), motivated by the benefits they would get intrinsically from formalizing the mathematical work they do into the OMDoc/MMT language (e.g. addressability of mathematical models), but also with an eye on all the other work packages from OpenDreamKit (e.g. interactive documents). Personally, I was focused on working out what I could of a semantic interchange between Sage and GAP of mathematical objects.

Formalization of mathematical concepts

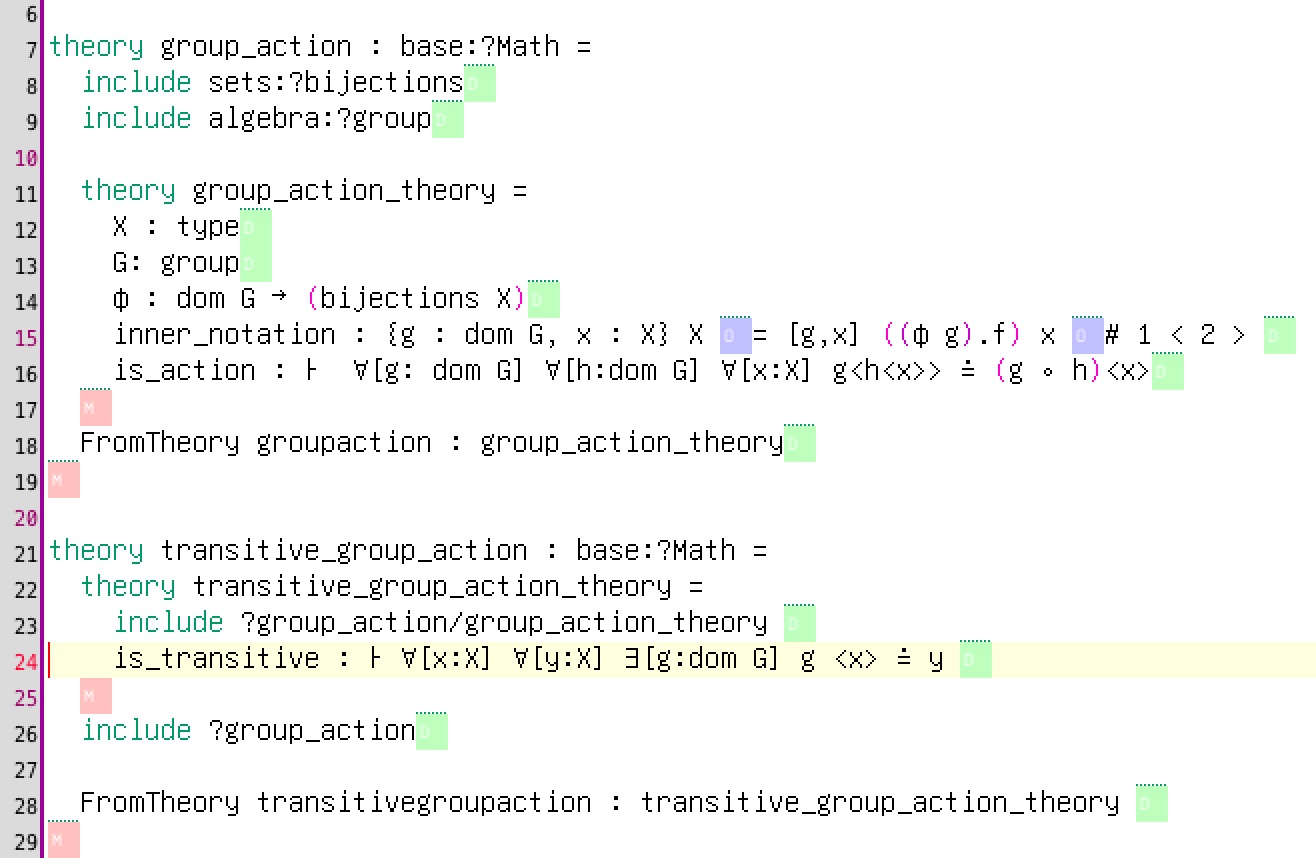

To start, we decided to do a bit of prototyping around transitive groups. The first step in the Math-in-the-Middle methodology for interoperability between computer algebra systems is to formalize the mathematical concept itself. Recent progress on the MMT language has actually made this very practical (see also here):

A mathematician should be able to point to this and get near universal agreement in the community on what that means.

Line 24 is of course critical to the definition, but one can see that the rest is well structured and readable. I have omitted here the first five lines, which consist of include statements, and make the whole thing a completely formal definition yet implemented at a very high level of abstraction. You could slim down those includes and build the same thing on flexiformal foundations, e.g. not bother with the logic “deep down”.

Overall, not many mathematicians might be able to write this, but almost any mathematician can navigate her way through it. It also helps that the jEdit editor and the MathHub webserver have drastically improved, especially in ease of use (work done as part of Work Package 4), but also installation and resilience (work done as part of Work Package 3).

Math-in-the-Middle methodology

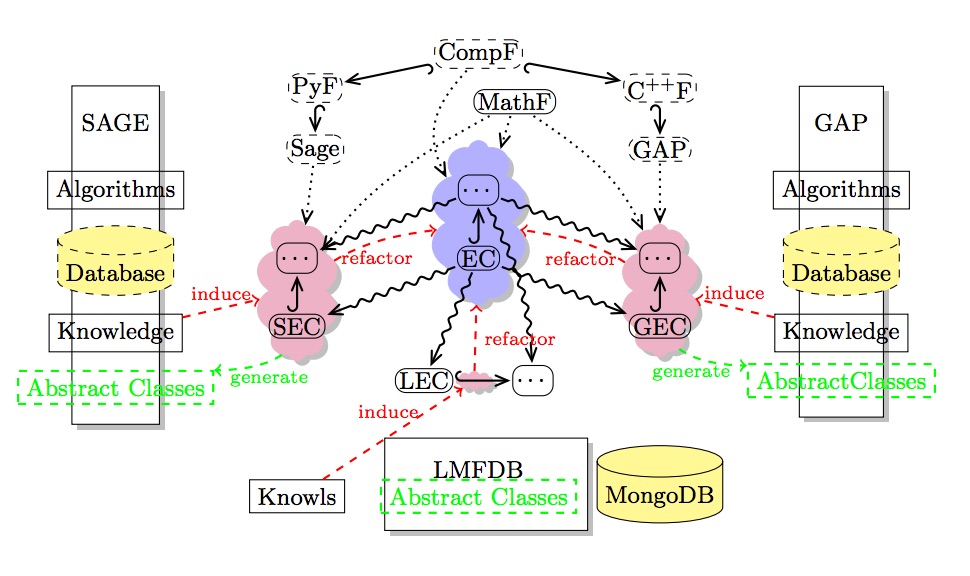

Now that we have a target formalization, the idea is to separately make Sage and GAP interact with it. In the Math-in-the-Middle (MitM) formalism adopted for Work Package 6, we think of having in the “center” a system-independent flexiformalization of the mathematical domains (represented in this diagram in blue; replace in your head EC for elliptic curves with TG for transitive groups).

The next step is to work on the reddish clouds, which are the interface theories between this center and the other systems. These interface theories mainly flexiformalize the system-specific aspects of the domain.

On the GAP side, GAP generates for those interfaces OMDoc/MMT Content Dictionaries (CDs) that contain name, type, and documentation for all API functions (constructors, predicates, methods, …). This is automated, has good coverage and is very rich semantically (more on that towards the end of the post). The next step of the plan is then to align the generated system CDs with the MitM formalization by the MMT implements relation of aligment (e.g. an aligment could be: GAP-transitive_group MMT-implements MitM-transitive group). If equivalent Sage CDs were available, as well as Sage alignments, we would get a semantic crosswalk between GAP and Sage by composing the MitM alignments between all those different CDs. This would provide the necessary framework for interoperability.

At the moment Sage does export some of its knowledge into CDs, thanks to what was implemented by Nicolas Thiéry, leveraging his category framework. This is unfortunately not enough to cover transitive groups, which have rich structure as category objects (but the “Category of Transitive Groups” does not exist in Sage). Given the circumstances of this workshop, I thus decided to focus on the Sage side, and see what information I could extract about transitive groups.

Exporting knowledge from Sage

If you look at Sage’s TransitiveGroup, a lot of mathematical knowledge is acquired from elsewhere through the class hierarchy lying above TransitiveGroup, and the category framework that instruments that hierarchy. This lead me to first try to build a model of how the Sage class TransitiveGroup was actually implemented and what it was doing, but this was a mistake. Indeed, it was very difficult, as I got lost between meta-logics and what I was actually trying to do: modeling Sage? modeling how Sage models math? how python uses Sage to model math? I was trying to do too much, too early and was probably the wrong person to do that.

If you look back at the methodology, the MitM CDs don’t need to link up to the Math-in-the-Middle content dictionary right away. This is actually up to the alignments, that come later (and could be done by a different person). I was trying to do both at once, while my focus should really have been: “how do I export, but not align, as much of the math knowledge as possible embedded into Sage into a language that can easily be processed by the KWARC team?” (for the categories export built by Nicolas Thiéry, the export went through JSON).

OK then, the question now becomes: “where is math knowledge embedded in Sage that is relevant to the mathematical concept of transitive group?” The first response is of course still “Everywhere!”, but where are actually the low hanging fruits?

A math skeleton

I found that the best way to communicate around this issue with the KWARC team is by extracting from Sage code a “math skeleton”. For this, the Sage-specific module sageinspect was very useful. I thus introspected the sage object corresponding to the class TransitiveGroup, and related objects:

# sage/src/sage/structure/sage_object.pyx

cdef class SageObject:

# sage/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sage/categories/category.py

class Category(UniqueRepresentation, SageObject):

# sage/src/sage/structure/category_object.pyx

cdef class CategoryObject(SageObject):

# sage/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sage/structure/parent.pyx

cdef class Parent(category_object.CategoryObject):

# sage/src/sage/groups/group.pyx

cdef class Group(Parent):

# sage/src/sage/groups/group.pyx

cdef class FiniteGroup(Group):

# sage/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sage/groups/perm_gps/permgroup.py

class PermutationGroup_generic(group.FiniteGroup):

# sage/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sage/groups/perm_gps/permgroup_named.py

class PermutationGroup_unique(CachedRepresentation, PermutationGroup_generic):

# sage/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sage/groups/perm_gps/permgroup_named.py

class TransitiveGroup(PermutationGroup_unique):

What is mathematical here? Clearly, just about everything, but that is because I was selective in the printout given above: I worked up the class hierarchy from TransitiveGroup by hand, but excluded all the python objects that don’t inherit from SageObject. For instance, you don’t see in that list:

# sage/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sage/structure/unique_representation.py

class CachedRepresentation:

CachedRepresentation is only relevant, from a mathematical standpoint, in where it appears as a superclass. Its own internals are pure design decisions for CAS software, not mathematics.

The criterion to use for “related objects” is thus that only objects inheriting from SageObject need to be navigated. So we are navigatin in the class hierarchy diamond between TransitiveGroup and SageObject, collecting classes, which I manually imported from the sage library (obviously this could be automated):

from sage.structure.sage_object import SageObject

from sage.structure.category_object import Category # not strictly in the class hierarchy, but included to facilitate discussion

from sage.structure.category_object import CategoryObject

from sage.structure.parent import Parent

from sage.groups.group import Group

from sage.groups.group import FiniteGroup

from sage.groups.perm_gps.permgroup import PermutationGroup_generic

from sage.groups.perm_gps.permgroup_named import PermutationGroup_unique

from sage.groups.perm_gps.permgroup_named import TransitiveGroup

This is how I selected the objects from which I wanted to extract more information, producing the list of class definitions above.

[Note by the way the weird changes in the path to sageinspect.sage_getsource in the listing above (why??? because of interactions between import statements?)]

More flesh on the skeleton

The next step is to add a bit of flesh to that skeleton export. Obviously this is going to be more intricate. I have included here what you get when you look at all the methods coming out of the source code for TransitiveGroup, PermutationGroup_unique, etc. In other words, a completely static navigation to the specific methods. This was the right thing to do for communicating with the KWARC team, but is wrong for our ultimate purpose. It was the right thing to do to communicate with KWARC (or in a blog post) as it distilled Sage to its most interesting bits, and we could fill the gaps relying on comment concepts (like “class hierarchy”). However, as a quicker way to get more consistent and richer Sage output, I could have navigated dynamically to the relevant classes, and extracted all the methods available from the live objects. This is of course because tons of methods get added when the object gets created, with a lot of mathematics packed into that. The same math could be reconstructed from the source code, but obviously that would be harder to do as we would be re-emulating a lot of what python does.

In any case, here is the full printout of what I get for just the method declarations for PermutationGroup_generic, the Parent that is most interesting:

# sage/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages/sage/groups/perm_gps/permgroup.py

class PermutationGroup_generic(group.FiniteGroup):

def __init__(self, gens=None, gap_group=None, canonicalize=True, domain=None, category=None):

def construction(self):

def _has_natural_domain(self):

def _gap_init_(self):

def _magma_init_(self, magma):

def __cmp__(self, right):

def _element_class(self):

def __call__(self, x, check=True):

def _coerce_impl(self, x):

def list(self):

def __contains__(self, item):

def has_element(self, item):

def __iter__(self):

def gens(self):

def gens_small(self):

def gen(self, i=None):

def identity(self):

def exponent(self):

def largest_moved_point(self):

def degree(self):

def domain(self):

def _domain_gap(self, domain=None):

def smallest_moved_point(self):

def representative_action(self,x,y):

def orbits(self):

def orbit(self, point, action="OnPoints"):

def transversals(self, point):

def stabilizer(self, point, action="OnPoints"):

def base(self, seed=None):

def strong_generating_system(self, base_of_group=None):

def _repr_(self):

def _latex_(self):

def _order(self):

def order(self):

def random_element(self):

def group_id(self):

def id(self):

def group_primitive_id(self):

def center(self):

def socle(self):

def frattini_subgroup(self):

def fitting_subgroup(self):

def solvable_radical(self):

def intersection(self, other):

def conjugacy_class(self, g):

def conjugacy_classes(self):

def conjugate(self, g):

def direct_product(self, other, maps=True):

def semidirect_product(self, N, mapping, check=True):

def holomorph(self):

def subgroup(self, gens=None, gap_group=None, domain=None, category=None, canonicalize=True, check=True):

def as_finitely_presented_group(self, reduced=False):

def quotient(self, N):

def commutator(self, other=None):

def cohomology(self, n, p = 0):

def cohomology_part(self, n, p = 0):

def homology(self, n, p = 0):

def homology_part(self, n, p = 0):

def character_table(self):

def irreducible_characters(self):

def trivial_character(self):

def character(self, values):

def conjugacy_classes_representatives(self):

def conjugacy_classes_subgroups(self):

def subgroups(self):

def _regular_subgroup_gap(self):

def has_regular_subgroup(self, return_group = False):

def blocks_all(self, representatives = True):

def cosets(self, S, side='right'):

def minimal_generating_set(self):

def normalizer(self, g):

def centralizer(self, g):

def isomorphism_type_info_simple_group(self):

def is_abelian(self):

def is_commutative(self):

def is_cyclic(self):

def is_elementary_abelian(self):

def isomorphism_to(self, right):

def is_isomorphic(self, right):

def is_monomial(self):

def is_nilpotent(self):

def is_normal(self, other):

def is_perfect(self):

def is_pgroup(self):

def is_polycyclic(self):

def is_simple(self):

def is_solvable(self):

def is_subgroup(self, other):

def is_supersolvable(self):

def non_fixed_points(self):

def fixed_points(self):

def is_transitive(self, domain=None):

def is_primitive(self, domain=None):

def is_semi_regular(self, domain=None):

def is_regular(self, domain=None):

def normalizes(self, other):

def composition_series(self):

def derived_series(self):

def lower_central_series(self):

def molien_series(self):

def normal_subgroups(self):

def poincare_series(self, p=2, n=10):

def sylow_subgroup(self, p):

def upper_central_series(self):

Here are things a semi-intelligent mathematician can deduce from this fleshed-out skeleton, and that we might be able to export automatically:

- The arity of all those functions is useful. Unfortunately, this being python (2.x), the type cannot simply be read. Michael Kohlhase has some interesting ideas regarding mathematicians, types and the modeling necessary for MMT. I think he is right, partly, and there is much to look forward to in the services MMT can provide around type inference. Note that it will be core to this process that MMT allows for flexiformalisation as well!

- I omitted docstrings in this export, but of course this is also useful for semantic information in natural language. Often the docstring contains structured information too, for instance some typing information (see above).

- There is, as often, a method called

__init__that specifies a constructor. In other words, some combination of maps from some parameter space into the object modeled byPermutationGroup_generic. That relationship is messy though, most of the time. Note that the GAP team took the opportunity over last summer to have an intern refactor/regularize the way they did constructors into a more “semantic” way”: essentially instead of using the elementary__init__, they made adefconstructorand gave it documentation, type information,… as parameters. Of coursedefconstructorelaborates to a call to__init__but the parameters can be used in the CD generation (and for static type-based optimizations later; ask Markus Pfeiffer @ St. Andrews if you are interested in the details). _gap_xxxxand_magma_xxxxindicate that the relevant “stuff” exists in the corresponding CASes. This is thus indicating a good place to bootstrap the alignment process betweengapandsage, and therefore extract KPIs and generally optimize our progress. This would be best done by instrumenting at theSageObjectlevel, since this is where all those_other-computer-algebra-system_xxxxmethods are first located, as abstract methods.- the presence of magic methods

__xxxxxxx__indicates the existence of a relation of some kind on the elements ofPermutationGroup_generic, which is a SageParent. However, this information is best extracted from the categories export itself, presumably all(?) the time. is_xxxxmethods indicate the existence of a test and thus a property.- after some very basic pruning, all the other methods indicate the existence of clear mathematical objects, often relatively simple maps.

Many of the deductions made above will be done in the same way for all Parents (at least if we go for the easiest information to grab), so that’s where the instrumentation should go. Most of that instrumentation actually makes sense to have in a CAS, beceause it exposes mathematically relevant concepts. It would simply be used by the exporter generating the Content Dictionary.

Remark: Ultimately we want to extract information from live objects. It should not be lost, however, that what we are trying to do is partly a social process (the study of this process is itself the topic of Work Package 7). Humans have built the code from which we are trying to extract information, and now we want to communicate that with other humans so they can in turn code on top of that. Those other humans are familiar with different tools. For instance the KWARC team uses MMT related tools, like MathHub, but not Sage. Presumably other CAS developers or even “plain” mathematicians will just see Sage through an interface built on top of MMT. So I would advocate that we:

- Make sure to export all the information containing math from Sage into MMT, even that which is not readable beyond text by the system we export to;

- Devise methods to make this informal export as addressable as possible from within MMT, but not necessarily runnable.

Step 1. could be useful for instance if one is working in GAP and asking “How does Sage do that?”. We should be able to access Sage source code from within GAP, and it will be useful for automating some tasks.

Step 2. would be useful for students in the KWARC group, for instance, who would then be able to extract semantically richer information from a system like Sage with just verbal instructions from domain specific experts, because the data is now in MMT format. It splits the step in two: MMT extraction and semantic extraction, and requires different skills.

The process could be further accelerated, I bet, by exposing also deep sage introspection tools into MMT.

At this stage self-preservation instincts kick in and I don’t want to think deeper at this proposal from a logical standpoint.

I wish to thank Michael Kohlhase for suggestions that have improved the first draft of this post.

Workshops and Conferences Blog SageMath WP6: Data/Knowledge/Software bases Math-in-the-Middle Emerging Technologies